Naturalism, mental causation, free will. An inspiring guest contribution by Prof. Dr. Timm Grams.

My friend, who has a humanistic education, teases me by dropping snippets of Latin every now and then - my high school education is not good enough for that. Mind versus matter, an old philosophical argument shines through. Different frames of thought open up different perspectives. The fact that our views nevertheless converge surprisingly often creates a certain degree of accuracy in judgment.

Ignorabimus?

On occasion I hear or read the quote "Ignoramus et ignorabimus" from him. I look it up and find out what that means: “We don't know and we will never know.” This saying is the culmination of a lecture by a certain Emil du Bois-Reymond almost a century and a half ago. This is how I hear about this great physiologist and philosopher who uncovered the electrical nature of nerve signals and thereby made them amenable to measurement.

Du Bois-Reymond then formulated what eight years later he called the fifth in a series of seven world riddles: the origin of simple sensory perceptions. He writes (du Bois-Reymond, 1982, p. 35 ff.): “I feel pain, feel pleasure, taste sweets, smell the scent of roses, hear organ music, see red [...] It is absolutely and forever incomprehensible that it a number of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, etc. atoms should not matter how they lie and move, how they lay and move, how they lie and will move. There is no way to see how consciousness can arise from their interaction.”

Du Bois-Reymond sees the limits of knowledge of nature here and he ends his lecture with the striking "Ignorabimus!"

As direct and genuine as the red hat, the nod of approval, the skyline of Frankfurt, the throbbing tones of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony appear to us, for me everything boils down to the question of whether my neighbor feels the color red the same way I do , or whether his experience of the same situation differs from mine.

Why people are reluctant today to put an exclamation mark after Bois-Reymond's Ignorabimus and prefer a question mark is also because we are getting better and better at grasping how the excitation patterns in the brain are related to the situations encountered. However, this growing knowledge seems to me to be more of a sideways movement. It still tells us nothing about the nature of experience. The spiritual processes cannot be understood from their material conditions. Consciousness remains mysterious.

For du Bois-Reymond, our knowledge of nature is subject to a hard limit. He clarifies this with this picture (1882, p, 38): Even at the highest conceivable level of our own knowledge of nature, our “efforts to rise above this barrier are like an aeronaut striving for the moon”.

The airshipman at least has the moon in his sight. Peter Bieri thinks that we don't even know the place of longing (1992, p. 56): "Something applies to the riddle of consciousness that does not apply to other riddles: we have no idea of what would count as a solution, as understanding. "

Dead ends

All metaphysics provide a limitation of thinking. Anyone who willfully narrows their frame of thought will not get any closer to solving the riddle of the world. The naturalist undertakes such a failed attempt to solve the riddle of the world. He already fails at the level of logic; Experience and facts are not needed to prove his mishap.

The naturalist builds his knowledge on the metaphysical assumptions that there is only one world, that it is uncreated and governed by laws. Above all, this world – reality – should be “outside our thinking” (Mahner, 2018, p. 46); it is consequently “in its existence and its properties independent of our consciousness” (Vollmer, 2013, p. 22).

I'm reluctant to say it doesn't add up. It's too obvious. If there is only one world to be known, where do thoughts about that world find their place? Their place cannot be in the world, because the world is supposed to exist independently of consciousness and the thoughts contained in it. There is no place anywhere else, since there is only this one world. From this follows thoughtlessness. The concept of "consciousness" is therefore obsolete. But without thought there is no philosophy. Naturalism obliterates itself. Funny that there are these naturalists: philosophers without philosophy.

Since I'm at my favorite pastime, picking apart naturalism, I turn to another world enigma that the naturalist flatly denies, rather than solve, the existence of.

The seventh enigma concerns the question of free will (du Bois-Reymond, 1882, p. 84). Here, too, the naturalist has a simple solution: there is no such thing as free will. Schmidt-Salomon writes: The concept of free will is the “supposition that a person could have made a different decision under exactly the same conditions than he actually did” (p. 102). He holds that identical causes necessarily have identical consequences.

That may well be the case. However, no test arrangement can be imagined with which a person's decision could be checked by creating identical conditions. It would have to be the same person. But after the first run, their mental equipment has already changed, so that they cannot be considered for the following test run. The Popper criterion is inexorable: the naturalist's statement is metaphysical, unscientific, a matter of faith.

For both mysteries, the naturalist's solution amounts to denial: there is no consciousness, just as there is no free will. This violates common sense so blatantly that it refuses to follow the naturalist. The fact that naturalists get hopelessly tangled up when it comes to the spiritual has already been discussed several times in this weblog, including in the article Der Spiegel der Natur.

A fundamental consideration by Peter Bieri fits in with this. From him is this trilemma:

- Mental phenomena are non-physical phenomena.

- Mental phenomena are causally effective in the realm of physical phenomena.

- The realm of physical phenomena is causally closed.

Each of these statements seems reasonable on its own. Unfortunately they can't all be valid: 1&2 rules out 3; 1&3 excludes 2 and 2&3 excludes 1.

The naturalist rejects 2; so 1 and 3 remain. Since he recognizes only one world, there are no nonphysical phenomena. Consequently there can be no mental phenomena. Statement 1 thus becomes meaningless. This shows again: consciousness and free will do not exist for the naturalist; at best, they are illusions that the body provides for us (Schmidt-Salomon, 2006, p. 12). The naturalist thus lures us into a thought loop: an illusion that nobody perceives is not an illusion. We ask about the addressee of the illusion and end up back at the beginning of our search, with the question of the nature of consciousness. We become victims of word acrobatics without any deeper meaning.

Sideward movement

Under the shackles of metaphysics, we get at best pseudo-solutions for the riddles of the world. Let's get rid of it. Science knows no such limitations. Only the lack of contradiction and agreement with the facts mark out the frame of thought. There are, it seems to me, quite a few scientists struggling with the mystery of the world. I will only mention two of them here: Wolf Singer and Roger Penrose.

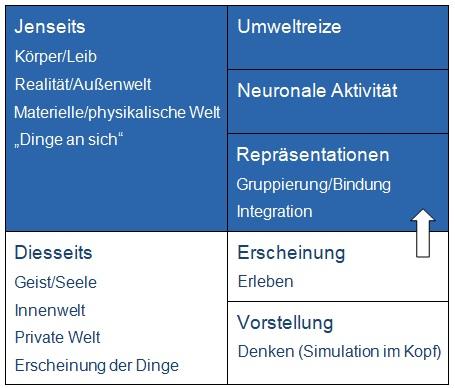

Man's thinking about his thinking has its difficulties. To keep the confusion within bounds, I have grouped the most important terms in a table. The left column gives the rough division between the outer world and the inner world: From the first we only have the "images in our heads", the appearances. They form the inner world. (Florey, 1997; Grams, 2020, pp. 248ff.)

The right column contains the segment of the world relevant to the study of consciousness. Here, too, the upper part with a dark background relates to the outside world, which is not directly recognizable, and the lower part to the inner world.

(I justify my use of language regarding "this world" and "hereafter" with the fact that it is only a small intellectual step from the incomprehensible reality to God. The gap between this world and the hereafter is huge in comparison.)

Let's let Immanuel Kant have his say. He writes in his work "Critique of Pure Reason" (2011, "Appendix. From the amphibolism of the concepts of reflection", p. 283): "But if we could also say something synthetically about things in themselves through the pure understanding (which nonetheless impossible), this would not be able to be applied to appearances that do not represent things in themselves. In this latter case, therefore, I will always have to compare my concepts in transcendental reflection only under the conditions of sensibility, and so space and time will not be determinations of things in themselves but of appearances: what things may be in themselves is known I don't and don't need to know, because nothing can ever appear to me other than in appearance."

The white arrow alludes to this thought of Kant: Since we only experience the appearances and not "the things in themselves", we group the supposed things of the outer world according to the appearances. So we “think” in the direction of the arrow.

The cause-effect direction is exactly the opposite. Science has made great strides in elucidating these causal relationships since the mid-19th century. The electrical nerve impulses resulting from an environmental stimulus can be measured. The causal dependence of nerve impulses on environmental stimuli is no longer a great secret. The sensory input ensures specific activity patterns of the nerves. This provides the brain's internal representations of the input.

Objects in the environment are not immediately recorded in their entirety. The brain is organized according to the division of labour. A passing taxi excites the nerve cells that sense color, contour, orientation, movement, etc. This happens in separate areas of the brain. How these partial representations become the representation of the object is one of the great mysteries of neuroscience (Ramachandran, Blakeslee, 1998, p. 80).

Even if this riddle will one day be solved to everyone's satisfaction, the crucial step is still missing. Strictly speaking, this didn't get us any closer to our goal. It amounts to a sideways movement, like that of the airshipman who just can't get any closer to the moon.

Andreas Engel, Peter König and Wolf Singer (1993) provide such a sideways movement. They write: "Correct assignment requires a mechanism that selectively identifies those cells in the multitude of activated cells that respond to one and the same object."

They see the oscillatory firing of the nerve cells as a binding agent. Synchronized firing separates those who belong together from the rest - this is the hypothesis. The partial representations can thus be combined to form an overall picture. But that does not elevate representation beyond the physical and physiological level. The event remains located in the afterlife.

New ideas needed

A lot has happened in science since the time of du Bois-Reymond. Milestones are the theory of relativity and quantum mechanics. Nevertheless, we humans have not come much closer to an understanding of consciousness. We are still "aeronauts aiming for the moon".

This year's Nobel Prize winner, Roger Penrose, writes in the foreword to "The Emperor's New Mind" that today's physics does not do justice to the phenomenon of consciousness (2016, p. xv): "The conscious aspects of our minds are not explicable in computational terms and moreover that conscious minds can find no home within our present day scientific world view.” And further (p. 580): "One can argue that a universe governed by laws that do not allow consciousness is no universe at all. I would even say that all the mathematical descriptions of a universe that have been given so far must fail this criterion. It is only the phenomenon of consciousness that can conjure a putative ‘theoretical’ universe into actual existence.”

As long as the laws of the world that we recognize do not allow conscious thinking, the universe cannot be thought either. So it doesn't exist for us. Today's science is obviously not rich enough to understand the spiritual.

Timm Grams studied electrical engineering at the TH Darmstadt (Dipl. - Ing.) until 1972 and received his doctorate in 1975 at the University of Ulm (Dr. rer. nat). Simulation, reliability technology and process data transmission were his main areas of work in industry. Since 1983 he has been a professor at the Fulda University of Applied Sciences in the fields of communications engineering, program construction, simulation and problem solving. Thought traps and rules to avoid them have been his passion for forty years. He also writes about this on his blog Hoppla!, where this post appeared before. The title image is from qimono on Pixabay.